Our GFCF Speaker Series for the 2025-26 Academic Year: The purpose of GFCF (aka The Forum) is dialogue across disciplines, ideologies, and philosophical persuasions, engaging key issues in scholarship and society from an orthodox Christian faith. We continue to explore new ideas, offer fresh, well-researched perspectives on current issues. Our target audience for this pertinent dialogue includes the senior members of the UBC teaching and research community: faculty, postgraduate students and postdoctoral fellows. We welcome alumni to participate as well. Our January speaker, Dr. Kevin Vanhoozer, will deliver a newly-minted paper. The venue is on Zoom, and the recordings will be posted on YouTube to allow a broader, international audience to participate. A few of our previous speakers have drawn over one thousand views in this way. Participants for this year are teaching in Israel, South Africa, Chicago, and Virginia. They bring a global perspective to their critical insights. It is our privilege to engage with these accomplished scholars. GFCF welcomes your questions and insights.

Notice: To be added to our mailing list, write: gfcfevents@gmail.com

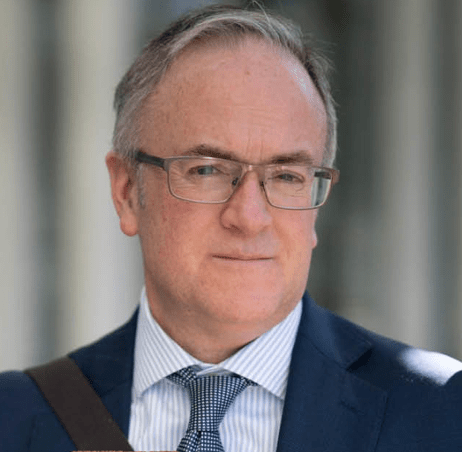

Kevin Vanhoozer

Three Documents of the University: Reading Nature, Culture, and Scripture Theologically.

Tuesday, January 27, 2026 @ 12:00 PM

Abstract

Universities arguably exist to make the universe legible (readable) and intelligible (understandable). In Christian tradition, what the Second Helvetic Confession calls the “Book” of nature is as readable as the book of Scripture, for both ultimately precede through the Logos in whom all things hang together. The “book” of culture, human history, is similarly legible, because it is written by those created in the image of the Logos. Modern secular universities, however, struggle to make sense of these three documents. What Hans Frei termed the “eclipse” of biblical narrative led to a “great reversal” in hermeneutics in which the biblical narrative gave way to other frames of reference. This presentation argues that the prevailing metaphysical frames of reference used today in the natural and human sciences, as well as in biblical studies, are ultimately unable to read rightly their respective texts. Brief examples from each of the three books – the laws of nature; human dignity; the historical Jesus – illustrate both the problem and also the way forward. This involves a retrieval of a theological frame of reference that privileges biblical narrative and enables faith-fuelled scholarship to gain a deeper understanding of reality.

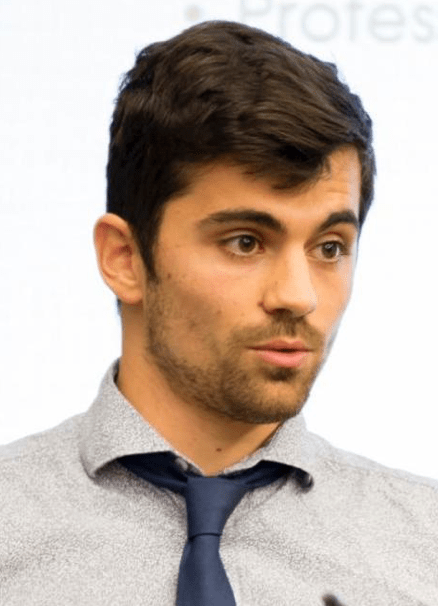

Response: Jens Zimmermann, PhD University of British Columbia, PhD Johannes Gutenberg. He is the J.I. Packer Chair of Theology at Regent College. Trained in both Comparative Literature and Philosophy, his research focusses on theological anthropology and epistemology, of who we are and how we know. Among other works, he has published books on university education (The Passionate Intellect: Incarnational Humanism and the Future of University Education, with Norman Klassen, Baker Academic 2006), the importance of humanism for Western culture (Humanism and Religion: A Call for the Renewal of Western Culture, Oxford University Press, 2012), hermeneutics (Hermeneutics: A Very Short Introduction, OUP 2014), and the theology of Dietrich Bonhoeffer (Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s Christian Humanism, OUP 2019).

Biography

Kevin J. Vanhoozer (Ph.D., Cambridge University on Paul Ricoeur) is Research Professor of Systematic Theology at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. Previously, he served as Senior Lecturer in Theology and Religious Studies at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland (1990-98) and as Blanchard Professor of Theology at the Wheaton College Graduate School in Chicago (2009-2012). He is the very articulate author of twelve books, including The Drama of Doctrine: A Canonical-Linguistic Approach to Christian Theology; plus Faith Speaking Understanding: Performing the Drama of Doctrine, and his impressive 2024 volume Mere Christian Hermeneutics: Transfiguring What it Means to Read the Bible Theologically. He is presently at work on a three-volume systematic theology. In 2017, he chaired the steering committee and drafted A Reforming Catholic Confession to mark the 500th anniversary of the Reformation. He is currently Senior Fellow of the C. S. Lewis Institute. He is an amateur classical pianist, and finds that music and literature help him integrate academic theology, imagination, and spiritual formation.

The ancients inhabited a ‘saturated’ frame of reference in which earthly, natural things are transitory signs of an eternal, supernatural realm of higher realities. Charles Taylor—”Modernity is an 18th century revolution in our social imaginary.” (K. Vanhoozer, Mere Christian Hermeneutics, 79-80).

The Bible’s story, read theologically, is sufficient for enabling us to perceive reality differently–not as a closed patio-temporal material nexus, but as created, sustained, and directed by the triune God. ~Kevin Vanhoozer

_________________

Mere Christian Hermeneutics: Transfiguring What It Means to Read the Bible Theologically (published 2024 by Zondervan Academic) is Kevin J. Vanhoozer’s ambitious proposal for a “mere” Christian hermeneutic—inspired by C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity—that outlines essential, universal principles for reading the Bible faithfully as Scripture across all times, places, denominations, and Christians. It is very ambitious, taking me back through my whole history of theological training and decades of debate (even one between Hans Boersma and Iain Provan at Regent College).

The book addresses two major challenges in biblical interpretation:

- The diversity of interpretations even within single Christian communities. We seldom examine this phenomenon in our churches or think more deeply about the kind of Bible reading culture(s) that exists there.

- The plurality of “reading cultures” (denominational, academic/disciplinary, historical, and global), each with its own interpretive framework–critical to his thesis. This is what he means by the term ‘hermeneutics’.

Vanhoozer responds by advocating a unified yet diverse approach that bridges the somewhat painful and unnecessary modern divide between biblical studies (often focused on historical-grammatical exegesis) and theology (focussing on larger biblical themes). He critiques polarized “reading cultures” and calls both exegetes and theologians to return interpretation to the church as the primary community for faithful reading. There is a definite existential aspect of his approach. In the end, he wants us to get much more from reading and interpreting the Bible for life lived robustly.

The Central Metaphor and Thesis: The book’s core working image is the transfiguration of Jesus on Mount Tabor (from the Gospels), which Vanhoozer uses to reframe theological interpretation. Many interpreters miss this powerful biblical metaphor. He argues that figural (or “spiritual”) reading does not distort or deny the literal sense (sensus literalis) but glorifies and transfigures it—revealing its deeper, eschatological and Christ-centered meaning. He sees a ‘christocentric’ and ‘christoscopic’ nature to the larger biblical narrative.

He introduces “trans-figural” interpretation as a better alternative to traditional terms like typology or allegory:

- It “thickens” the literal sense by following biblical figures across the canon and across redemptive history to their fulfillment in Christ. He fulfills the law and the prophets, fills out their meaning.

- It views the literal sense not as merely historical/earth-bound but as eschatologically oriented toward God’s ultimate revelation in Jesus. Scripture is always connected with eternity, the transcendent.

- Interpretation therefore becomes a matter of seeing the light of Christ shining through Scripture, transforming both the text’s meaning and the reader. Vanhoozer sees a major emphasis on the “economy of light” across the biblical narrative–from Genesis to Revelation.

This leads to a vision where reading Scripture is intensely dialogical (a response to God’s powerful address and calling to humans), transformative (conforming readers to Christ’s image), and oriented ultimately toward worship, gratitude, and witness. He employs speech act theory (J. L. Austin) and terms like “communicative action” by God to reveal this dynamic. He is known for his very clever usage of contemporary literary devices as we dig deeper to understand Scripture as a living thing that moves a person’s universe.

Book Structure: The book is organized as an “experiment in biblical-theological criticism” divided into three parts:

Part 1: Reading the Bible inside and outside of Church — Surveys the “divided domain” of interpretation, critiques polarized reading cultures (e.g., between modern biblical scholarship and theology), and calls for church-centered approaches that form “gospel citizenship” rather than mere literacy. He appeals for a more mature “Bible reading culture.”

Part 2: Figuring Out Exactly What We Mean by Literal Interpretation — This is critical to his thesis. He redefines the sensus literalis beyond narrow grammatical-historical senses to include eschatological reference and figural depth, moving toward a “trans-figural” literal sense in a “reformed catholic” (Christ-focused, broadly orthodox) paradigm. That’s a mouthful.

Part 3: Transfiguring Literal Interpretation — Applies the transfiguration motif extensively:

- Explores light imagery in creation (e.g., Genesis 1:3).

- Examines the transfiguration accounts in the Synoptics and John.

- Shows how trans-figural reading “unveils” the glory in the letter (e.g., via Paul’s reading of Moses’ veil in 2 Corinthians).

- Concludes with how readers themselves are transfigured/transformed through faithful engagement with Scripture and obedience to its tenants (“with unveiled faces”). Kierkegaard would be happy with this stance.

The conclusion envisions “beatific lection”—reading that leads to beholding Christ’s glory and fostering transfigured Christian communities. If we read the Scripture properly, we should be permanently changed by the living, breathing Word of God.

Overall, Vanhoozer’s work is irenic (peace-seeking without shallow compromise), richly interactive with historical interpreters, intensely creative, and provocative. It is a great senior seminar textbook (ThM). It emphasizes that true interpretation glorifies God by enabling us to see and reflect Christ’s light in Scripture out into the world. Reviews, leading to its prize-winning status (Christianity Today’s Book go the Year), praise its depth, creativity, and potential as a landmark in theological hermeneutics, while noting its demanding style and Western focus. It’s aimed at pastors, scholars, and serious readers seeking to read the Bible theologically in a fragmented age, appealing to a much larger frame of reference than we often encounter in the university.

“To read the Bible as God’s word is therefore to encounter something that is living and active: the voice of God, God personally speaking, the triune God in communicative action, doing things with, in, and through human words.” (K. Vanhoozer, 2024, 9)